Recent tensions over land and maritime border disputes in Latin America threaten to upset the fragile peace between nations that has characterized the region for years. Enmity over these territorial boundaries has festered since the era of Latin American independence. Despite this tense environment, a January 2014 decision by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) managed to resolve one of the longest lingering border disagreements in Latin America, and other disputes are now waiting for arbitration. These events show that contemporary Latin American nations are more likely to seek to resolve their issues in international legal institutions rather than resorting to military force. For now, international structures—both legal institutions that resolve ongoing disputes and treaties that prevent nations from taking action—have deterred Latin American nations from fighting over territorial border disputes. In this case study, I’ll be exploring the recent resolution of the Peru-Chile maritime dispute.

On January 27, 2014, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) resolved a longstanding maritime dispute between Peru and Chile. In the late 1800s, Peru had lost a section of its territory to Chile as a result of the War of the Pacific, a conflict that took the lives of nearly 11,000 Peruvians. After two years of fighting for sea control, Chilean soldiers reached Peru’s capital city, Lima, and proceeded to sack and loot the city. Peruvian resistance forces in the Andean Cordillera continued fighting using guerilla warfare tactics for nearly three more years. When both countries finally agreed to truce terms in the 1883 Treaty of Ancón, Peru surrendered the province of Tarapacá and Arica to Chile. The province of Tacna was also under Chilean control until 1929.

On January 16, 2008, Peru introduced the case to the International Court of Justice in The Hague. The action proved to be extremely popular move for President Ollanta Humala; presidential approval ratings jumped six percentage points from 44% to 50% following the announcement of the legal actions. Some estimates indicate that an ICJ decision in Peru’s favor could generate $800-$900 million in local revenues. About two-thirds of Peruvians polled in a recent survey indicate they expected a ruling in Peru’s favor. Almost the same number believed that Chile would ignore any ICJ decisions unfavorable to them.

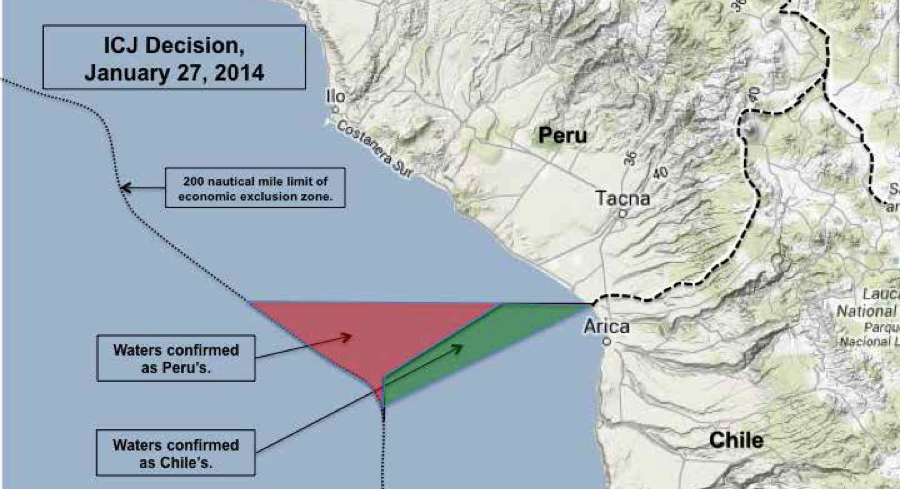

In its decision, the court appeared to try to find a compromise that would appease both countries. The court handed control to Peru of almost 19,000 square miles of ocean. Chile was able to keep control of approximately 6,000 square miles. Peruvian officials celebrated the court ruling, which cannot be appealed. Disappointed Chilean officials warned that it could jeopardize relations between the two countries. Soon after the decision, leaders from both nations met in private and reached an agreement in broad terms on how to implement the court’s decision.

Peruvian President Humala declared, “Peru and Chile have given an object lesson to the international community in how to confront and overcome their differences in the most constructive way possible, each defending their positions with responsibility, seriousness, and maturity.” In Chile, implementing the court’s decision falls to President Sebastian Piñera’s successor, Michelle Bachelet, the incoming president who assumed office on March 11, 2014.

The recent ICJ decision on the Peru-Chile maritime dispute reflects a new direction of international relations. In other case studies I examined for a longer piece in the Foreign Area Officer Association Journal of International Affairs, Latin American nations seem to accept arbitration by international legal institutions such as the International Court of Justice in place of unilateral action. For now, regional state actors choose to use international structures that promote peace rather than resorting to previous inclinations of aggression and conflict. These events show that contemporary Latin American nations are more likely to seek to resolve their issues in international legal institutions rather than resorting to military force.

This case study is excerpted from a longer piece, The Peru-Chile Maritime Border Decision and Latin America Border Conflicts, co-authored with Rory Flynn, that appeared in the Winter, 2014 edition of Foreign Area Officer Association Journal of International Affairs.