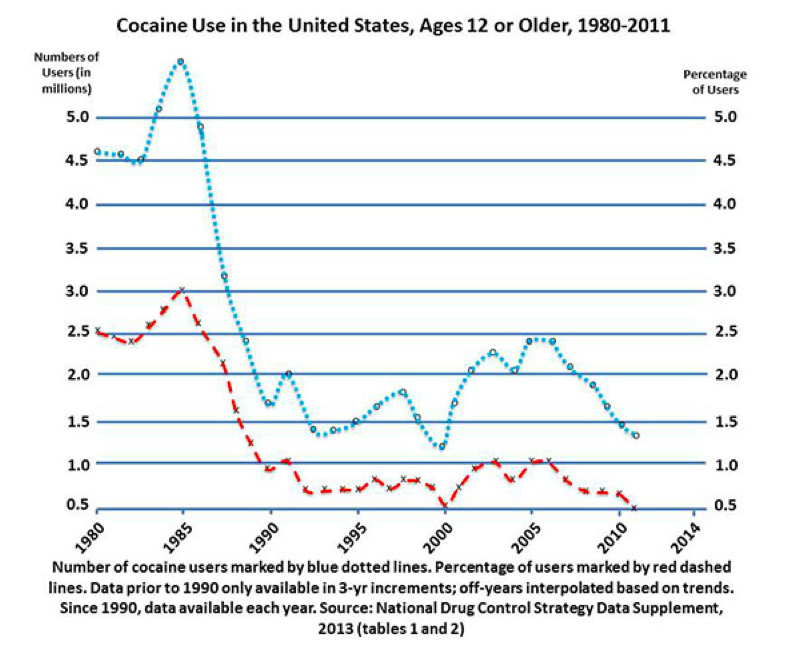

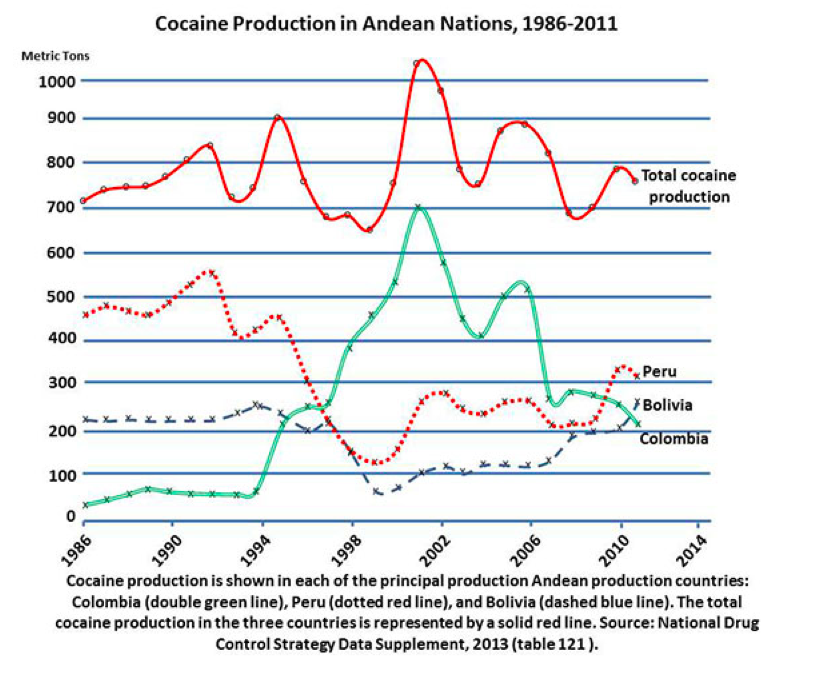

“The global war on drugs has failed.” The opening statement in a recent report by a coalition of former heads of state captures the sentiments of a growing number of Latin American leaders. After five decades of combating drug traffickers, Latin American allies who bore the brunt of the drug-fueled violence claim that counternarcotics efforts have not achieved any significant results. Critics say the effort cost a lot—perhaps as much as a trillion dollars according to one scholar—and has produced very little for the investment. Both the Organization of American States (OAS) and the United Nations (UN) have called for reforms to the current strategy. Some Latin American leaders openly support legalization or decriminalization of drugs, a policy at odds with U.S. counternarcotics strategy.

Counterdrug policy in Latin America is under scrutiny not only from Latin American leaders, but also globally. In late 2013, the UN announced that it would hold a General Assembly Special Session in New York in 2016—its first in almost 10 years—to address international drug problems. The event may be an ensemble directed at the U.S. to revisit drug policy reform. Knowing the careful political atmosphere in an election year in the United States, however, no dramatic announcements from the U.S. are likely to occur. International drug reform, Vice President Joe Biden said, is “worth discussing, but there is no possibility the Obama-Biden administration will change its policy.”

Individual states’ policies within the U.S. may be part of the problem. In the November 2012 elections, constituents in two U.S. states—Washington and Colorado—voted to legalize recreational use of marijuana. Eighteen other states and the District of Columbia have legalized medicinal marijuana. The rest of the country is watching closely how these two states manage their programs. Colorado officials, for example, leveled a 25 percent tax on the sale of marijuana that they claim will raise $6.5 billion in revenue for the state’s defunct school system. The apparent hypocrisy of the situation—the U.S. promotes a hard line on drug policy among its allies but permits legalization at home—drew an international rebuke. In March 2013, the UN’s International Narcotics Control Board called on the Obama administration to end legalization of marijuana within the states, claiming it undermined international efforts to curtail trafficking. President Santos of Colombia called the decision in Washington and Colorado a “major contradiction” in drug policies. “How can I tell the peasant that is growing marijuana in the mountains of Colombia that he will go to jail if smoking marijuana is legal in Colorado or Washington?” Santos asked.

Within Latin America, some nations have already moved beyond the U.S.-advocated strategy. In Uruguay, President Jose Mujica pushed a marijuana legalization bill through Congress. During the policy roll-out, Uruguayan Interior Minister Eduardo Bonomi announced, “The war on drugs has failed and now we have to find another path.” The measure, signed into law in December 2013, makes Uruguay the first country in the world to license and enforce rules for the production, distribution, and sale of marijuana for adults.

In the future, after further examination of the issues, the decision on drug decriminalization may appear easier to resolve. One day, it may be perceived the way the U.S. Prohibition of alcohol of the 1920s is regarded today, widely accepted as a counterproductive policy that was doomed to fail. In most countries, alcohol is widely regulated by the government. Despite its role as a source of social dysfunction—domestic violence, job-productivity loss, vehicular accidents—alcohol regulation is now widely institutionalized throughout the government. Marijuana and cocaine may go the same direction over the course of time. For now, there is no clear path or consensus on the problem among nations in the Americas. As President Santos of Colombia said of the current dilemma, “So are we going to continue 50 years more? Or are there better alternatives?” Policy changes may occur in the future, but for now it appears that we are destined to muddle through rather than make a clean break from the current war on drugs.

This blog post is excerpted from a longer piece. To read more about international counter-narcotrafficking efforts and the market for illegal drugs in the U.S., check out my recent piece, Measuring Success in the War on Drugs.