The Bad

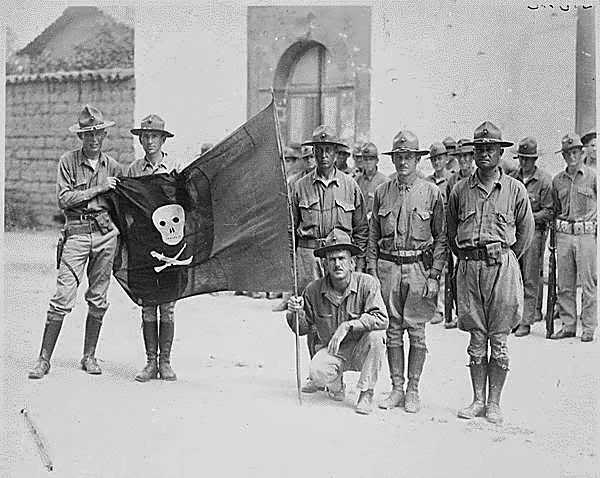

The United States is frequently criticized for its mixed record of human rights in Latin America. During the Cold War, we actively supported non-democratic leaders in the region (in some cases, tyrants who murdered thousands of their own citizens) as long as they supported Washington’s policies of communist containment. Additionally, although most countries in the region have ratified international human rights treaties, we've refused to join international or regional human rights treaties, including the American Declaration of Human Rights.

This puts us in a minority position relative to the rest of the western world. The other G7 countries have signed and ratified nearly all the major international treaties, while the United States has ratified less than half of them. In fact, the United States has ratified fewer human rights treaties than any Central or South American country. What is more, we've actively campaigned against human rights initiatives adopted by other Latin American nations, threatening to withdraw assistance from countries that try to hold the U.S. to the same standards as that of international treaties.

The Good

On the other hand, advocates of the U.S. record on human rights point to the fact that the United States has the oldest continuous constitutional tradition of a written bill of rights of any country in the world. Civil liberties are vigorously defended in U.S. courts, and we actively campaign for global human rights standards through foreign aid, sanctions, and even military intervention. Finally, supporters stress that the United States is home to the largest and most active community of human rights nongovernment organizations (NGOs) in the world today.

The Future

Where does this leave the United States, a country that has purported to champion human rights, yet one who has a mixed record of support for human rights initiatives? Critics of the United States contend that, with its long association with military leaders in the region and its mixed record on human rights, the United States has done more harm than good in the region. Except for responses to natural disasters, such as in Haiti in 2010, the United States never once intervened militarily in Latin America for strictly humanitarian reasons.

However, there is much more to the issue of human rights than an analysis of just civil or political liberties can summarize. Any attempt to do so would be a gross oversimplification of a complex and multifaceted topic. The United States generally does not often get credit for supporting Latin American countries against communist aggression during the Cold War. Nor does it receive credit for promoting democracy in the region nor for the economic assistance it has provided to countries in the region during times of trouble. Additionally, much of the U.S. military assistance in the region comes in the form of training that helps professionalize the armed services, teaching civil-military relations, rule of law, subordination to civilian authority, and even human rights. Indeed, the U.S. Southern Command headquartered in Miami, Florida, conducts security cooperation efforts with every nation in the region and is the only geographic combatant command with a permanent human rights office.

Our policymakers must realize that our foreign policy mistakes in Latin America have had significant blowback. In 2008, our ambassadors were kicked out of Venezuela and Bolivia. In 2008, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) was kicked out of Bolivia, one of the largest coca cultivation countries in the world. In November 2009, the United States was forced to depart an important strategic air base in Manta, Ecuador, when Ecuadorean President Rafael Correa refused to renew the lease to the base. Additionally, globalization of the world’s economic markets permit nations like China, Russia, and Iran to fill in the gaps left behind when theUnited States withdrew or was asked to leave. The takeaway from all this is that foreign policy mistakes can have long and expensive repercussions. Even though intervention could help accomplish near-term objectives in our foreign policy, the long-term results may be counterproductive to our strategic interests.

This blog post is excerpted from a longer piece. To read more about the United States' long and turbulent history with Latin America, check out my original op-ed piece, Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Policy in Latin America, (found on page 215.)